For the latest news from Scotland see our ScotNews feed at:

http://www.electricscotland.com/

Electric Scotland News

I've actually been reading rather than publishing this week. I got hooked on reading the biography of Lord Strathconna and Mount Royal which was a very enjoyable read. I'd previously put up a biography about him but that one almost ignored his early life in both Scotland and Canada. I was also taken with all the work he did for Newfoundland to promote the area economically. He also created an experimental farm which demonstrated that you could live well as long as you were well organised and so as one person put it when visiting him he enjoyed all the best in beef, pork and lamb along with fresh vegetables. I've made this book available and you'll see a link to it below.

-----

And as this coming Saturday usually sees the Burns Suppers being celebrated all over the world I've made available a great book by the Rev. Paul who is credited with starting the Burns Suppers. The book is...

The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns with a Life of the Author

Containing a Variety of Particulars, drawn from sources inaccessible by former Biographers to which is subjoined an Appendix of a Panegyrical Ode, and a demonstration of Burns' Superiority to every other poet as a writer of Songs, by Rev. Hamilton Paul, Minister of Broughton, Glenholm & Kilbuch (1819)

You can download this book from http://www.electricscotland.com/burns/paul.htm

Electric Canadian

The Life of Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal

When I first put up a biography of Lord Strathcona his early life was very bare of facts. I found a new book which now lets us learn much more about him both in his early days in Scotland but also in Canada. I now realise just how much he helped Newfoundland to grow their economy.

And so have now added this single volume work to the foot of his page at:

http://www.electriccanadian.com/make...cona/index.htm

In the Rocky Mountains

By W. H. G. Kingston (1878)

I just happened to find this book and thought it would make an interesting read so have made it available on the site for you to download at http://www.electriccanadian.com/pion..._Mountains.pdf

Electric Scotland

Scottish Reminincenses

By Sir Archibald Geikie (1904)

Now completed this book by adding the final chapters.

You can read this book at http://www.electricscotland.com/hist...bald/index.htm

Enigma Machine

Have added puzzle 95 which you can get to at:

http://www.electriccanadian.com/life.../enigma095.htm

Beth's Newfangled Family Tree

Got in Section 2 of the February 2015 issue which you can read at http://www.electricscotland.com/bnft

I might add that we got this in last week but Beth discovered she'd made some errors so has now released a new copy.

Kincardinshire

By George H. Kinnear, F.E.I.S. (1921). A new book we're starting.

Mr Kinnear’s death when he had written the text of this volume, but had not finally revised it, left the work to be completed by the general editor. Fortunately, the changes which Mr Kinnear intended to make were clearly marked; and these have been closely followed. As it has been impossible to find an accurate list of those who, by advice or otherwise, assisted Mr Kinnear, will all who did so kindly accept this general acknowledgment of their much-appreciated help?

The general editor is deeply indebted to his friend, Mr J. B. Philip, himself a son of the Mearns, who has given unstintedly of his full knowledge of the county and has rendered invaluable service in the reading of the proofs. In addition, Mr Philip generously presented a number of his own photographs for use in illustration.

W. MURISON

November 1920

As many of you will know I'm always looking for histories of places in Scotland and this is such a one that fills a gap. You can view this at http://www.electricscotland.com/hist...hire/index.htm

Notable Orcadians

From Around the Orkney Peat-Fires.

I came across this account which is about a group of Orcadians sitting around a peat fire talking about noteable Orcadians. I enjoyed the telling of the stories so decided to add this to our Orkney page. Here is how it starts...

One wild blustering night many winters ago a number of neighbours had gathered around a rousing peat-fire in the Herston district of South Ronaldshay. The conversation, as was quite natural, brought up the name of the Rev. John Gerard. One of the company, looking across the fire at old Watty Sinclair, asked that worthy whether he knew this once famous minister.

Slowly laying aside his pipe, and gazing at his questioner with open-eyed amazement at his ignorance (whether assumed or otherwise we need not stay to inquire), Watty exclaimed— “ Did I know Mr Gerard? Man, you might as well have asked if I know my own wife or my own bairns. A more sensible question would have been, Is there anybody in South Ronald-shay or in Orkney, that has not heard of him?”

It was quite plain that Watty was very much out of temper because such ignorance had been imputed to him. He had well-nigh worshipped Mr Gerard in life, and now that the eccentric old minister was gathered to his fathers, Watty would gladly have transformed him into an Orkney saint.

Mansie Louttit, who was a man of tact, and was well aware of his old friend’s peculiarities, mildly suggested that it would be well if the rising generation knew more of Mr Gerard than they did; and he was sure there was no one in Orkney better fitted to give that gentleman’s biography than Watty Sinclair.

This bit of flattery somewhat mollified Watty, and, as he was pressed by all present to tell the story of Mr Gerard’s life-work in the county, he cleared his throat, and began : —

You can read this at http://www.electricscotland.com/hist...ey/notable.htm

The Poetical Works of Thomas Aird

By The Rev Jardine Wallace.

I got an email in about another person that I'm researching which mentioned this person to me and so did some research and found a book of his poems which also included a memorial about him. I've ocr'd in this onto the site and also made available the whole book for you to download.

You can get to this at http://www.electricscotland.com/poetry/aird_thomas.htm

THE STORY

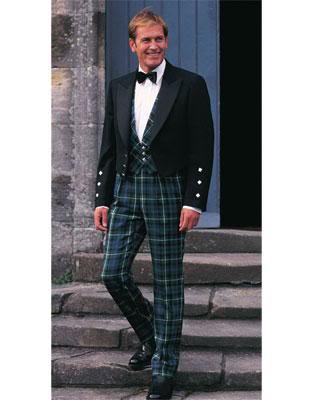

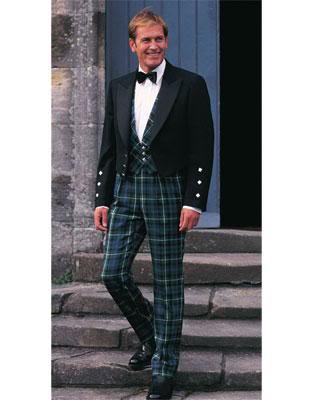

I've often wondered why more Scots don't wear this dress rather than the kilt and have often thought of getting this myself. As you'll read in the following article it is a quite ancient dress and an early use of tartan.

The Celtic Trews

An article from the Scottish Historical Review

WHEN the Baron of Bradwardine complimented Waverley upon the handsome figure he presented when fully attired as a Highland gentleman, he incidentally drew a comparison between the respective merits of the kilt and the trews, giving his decision in favour of the latter. ‘Ye wear the trews,’ he observed, ‘a garment whilk I approve maist of the twa, as mair ancient and seemly.’ There may be a difference of opinion at the present day as to which of these two varieties of Highland garb is the more seemly, but there is no doubt as to the antiquity of the trews, regarded as a part of the Celtic dress. Scott himself, speaking in his own person, states that Waverley had ‘now fairly assumed the “garb of old Gaul,” ’and there is sufficient evidence that this statement is correct, making due allowance for some modifications in vogue in the eighteenth century, and introduced at one time or another during that period and the immediately preceding centuries.

The dress of the Celts of Western Europe, about 2000 years ago, has been described by Mr. Charles Elton; his statements being drawn from such authorities as Diodorus Siculus, Pliny, and Pausanias, and from such evidences as the pictures on the medals of the Roman emperor Claudius. Mr. Elton writes as follows:

‘The men and women wore the same dress, so far as we can judge from the figures on the medals of Claudius. When Britannia is represented as a woman the head is uncovered and the hair tied in an elegant knot upon the neck; where a male figure is introduced the head is covered with a soft hat of a modern pattern. The costume consisted of a blouse with sleeves, confined in some cases by a belt, with trousers fitting close at the ankle, and a tartan plaid fastened up at the shoulder with a brooch.’ This form of Celtic dress is of special interest to all who are connected with the Scottish Highlands. Because, while it may have been worn by Continental Celts for many centuries after the date of Claudius, it eventually vanished from the Continent, and from all other parts of the British Isles except the Scottish Highlands, where it continued to be worn without any radical variation down to our own times.

The authority whom I have just quoted continues thus, with reference to the Celts of 2000 years ago: ‘The Gauls were experts at making cloth and linen. They wove their stuffs for summer, and rough felts or druggets for winter-wear, which are said to have been prepared with vinegar, and to have been so tough as to resist the stroke of a sword. We hear, moreover, of a British dress, called guanacum by Varro, which was said to be ‘woven of divers colours, and making a gaudy show.’ They had learned the art of using alternate colours for the warp and woof so as to bring out a pattern of stripes and squares. The cloth, says Diodorus, was covered with an infinite number of little squares and lines, ‘as if it had been sprinkled with flowers,’ or was striped with crossing bars, which formed a chequered design. The favourite colour was red or a ‘pretty crimson.’ In the words of Pliny, ‘Behold the French inhabiting beyond the Alps have invented the means to counterfeit the purple of Tyrus, the scarlet also and the violet in grain; yea, and to set all other colours that can be devised, with the juice only of certain herbs, such colours as an honest-minded person has no cause to blame, nor the world reason to cry out upon.’ ‘They seem to have been fond of every kind of ornament,’ continues Elton. ‘They wore collars and “torques ” of gold, necklaces and bracelets, and strings of brightly-coloured beads, made of glass or of “a material like the Egyptian porcelain.” A ring was worn on the middle finger [at one period, but in a later generation] the fashion changed, and that finger was left bare while all the rest were loaded.’

Such, then, was the attire of the Celts of 2000 years ago in time of peace. Of their armour, offensive and defensive, it would be out of place to speak here.

The accounts just cited, therefore, show us that the tartan was in full swing at that period in all its varied colours; red or crimson being chiefly preferred. And the dress was a sleeved blouse, often belted, with a tartan plaid thrown over it; the lower limbs being clad in trews, closely fitting at the ancle.

This last item requires to be emphasized, owing to popular misconceptions, not only among illiterate Cockneys, but also among many educated people in England, Scotland, and elsewhere. The Celtic people whom Pliny styles (in Holland’s words) ‘the French beyond the Alps’ were remarkable in the eyes of the Romans from the circumstance of their wearing the trews, an article of apparel of which the Romans were innocent. At Rome the word transalpinus, or ‘a person living beyond the Alps,’ was a synonym for ‘a person wearing breeches or trousers.’ The Celtic druids were nicknamed ‘the long-trousered philosophers’ and the Celts as a people were further nicknamed Bracati or Gentes Braccatae, ‘the trousered people.’ On the other hand, the Roman dress was the toga, or mantle, and the belted tunic, a garb very closely resembling the plaid and kilt which in later centuries became associated with at least one branch of the Celtic nation. So averse, indeed, was the early Roman to the restrictions of the nether garments of the Celts, that the first Roman emperor who so far forgot himself as to wear breeches at once raised against him a perfect storm of popular indignation. In fact it would seem to be the case that the wearing of these articles of apparel is a custom which the people of Europe have inherited from the Celts.

Whatever may have been the custom in the days of the Emperor Claudius, the trews has long ceased to be worn by Celtic ladies, unless occasionally in a metaphorical sense. One exceptional instance, it is true, is that of Miss Jeanie Cameron, whose name is so much associated with that of Prince Charles Edward; for she is pictured as attired 'in a military habit— tartan doublet and trews—fully armed, with a gun in her hand.’ But then, it was understood that she was dressed as a man.

The earliest representation of a trews-wearing Highlander which I am able to indicate seems to date from the sixteenth or possibly the seventeenth century, although the picture upon which this supposition is based was only printed in 1767. Curiously enough, it comes from Germany, having been printed on one of a pack of playing cards published in Nuremberg. It is entitled ‘Ein boser Berg-Schott,’ ‘a fierce Scottish Highlander.’ The figure is that of a man wearing what is clearly meant to be a tartan plaid and tartan trews, with a cap or bonnet, in which may be discerned the tail feathers of a black-cock. His face is clean-shaven, except for a small moustache. His right hand is engaged in drawing his sword, and with his left hand he is holding a pike, slanting over his shoulder. The butt of a pistol is seen projecting from his belt. One cannot say with certainty when the original of this picture was drawn, but it seems to contain inherent evidence that it describes a Highlander of at least a century before 1767.

The Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland show us, from entries made in August, 1538, the dress then worn by James the Fifth during a hunting excursion in the Highlands. He wore a ‘short Highland coat’ of parti-coloured velvet, lined with green taffety, trews of ‘Highland tartan,’ and a long and full ‘Highland shirt’ of holland cloth, with ribbons at the wrists. I have here used the word ‘trews,’ but the entry in the accounts is: ‘Item for 3 ells of Highland tartan to be hose to the King’s grace, price of the ell 4 shillings and 4 pence.’ This, I think, clearly indicates the trews. Stockings were known as ‘short hose,’ to distinguish them from ‘hose’ or trews.

‘Defoe, in his “Memoirs of a Cavalier,” written about 1721, and obviously composed from authentic materials, thus describes the Highland part of the Scottish army which invaded England in 1639, at the commencement of the great Civil War. . . . “They were generally tall swinging fellows; their swords were extravagantly and I think insignificantly [i.e. unmeaningly or needlessly] broad, and they carried great wooden targets, large enough to cover the upper part of their bodies. Their dress was as antique as the rest; a cap on their heads, called by them a bonnet, long hanging sleeves behind, and their doublet, breeches, and stockings, of a stuff they called plaid, stripped across red and yellow, with short cloaks of the same. These fellows looked, when drawn out, like a regiment of Merry-Andrews, ready for Bartholomew fair. There were three or four thousand of these in the Scots army, armed only with swords and targets; and in their belts some of them had a pistol, but no musquets at that time among them.”

The uncomplimentary comparison between these Highland soldiers and ‘Merry Andrews’ is obviously due to the resemblance between a man dressed in tartan trews and a Pantaloon, or Harlequin, in his chequered, tight-fitting suit. It is by no means unlikely that the Harlequin’s dress is a survival of the dress of the Celtic juggler. The prevailing colour in the tartan of these troops of 1639 is described as red and yellow. This suggests the MacMillan Clan. The M‘Leods, however, are most prominently associated with the Royalist cause during the English campaigns, and it is well known that, owing to the heavy losses sustained by them when fighting for King Charles at the Battle of Worcester in 1651, the M‘Leods were held exempt from warfare by the other western clans until time had tended to increase their numbers.

The portrait of Andrew Macpherson of Cluny, of the year 1661, gives one a good idea of the trews-wearing Highlander of this period. Somewhere about this period, also, ought to be placed the portrait of Fraser of Castle Leathers, which hangs in the Town Hall of Inverness. This chieftain is dressed in a slashed coat and waistcoat, with tartan trews, and he has also a small sporran or purse. The sporran seems to have been frequently worn with the trews.

If Defoe is right in picturing the whole of the 3000 or 4000 Highlanders in the Scottish army of 1639 as wearing the trews, he indicates that that garment was then common to all ranks. Such, however, was not the case in later years, as may be seen from many references.

Lord Archibald Campbell gives a reproduction of the two supporters of the arms of Skene of that Ilk, as these were pictured in Nisbet’s Heraldic Plates in 1672. The dexter supporter shows a man wearing a flat round cap or bonnet, a short plaid crossing his chest from the left shoulder to the right hip, its under fold coming from the right arm-pit down to the basket-hilt of his broadsword, which hangs at his left hip, suspended from a long shoulder-belt, apparently of ornamented leather, put on above the plaid. The plaid was fixed by a brooch or a silver bodkin, at its point of crossing on the breast; but this is not visible in the picture. The shoulder-belt is of course suspended from the right shoulder. He wears a short coat or jacket, having the sleeves slashed about halfway up, and with ruffs at the wrist. Possibly, however, these are the edges of his gauntlets. His costume is completed by a pair of tartan trews, with garters, the bows of which are very prominent, and his feet are encased in high-heeled shoes. In his right hand he holds a drawn dirk, the point downward; and his left supports the dexter side of the shield. It may be added that his hair hangs down to his shoulders, his upper lip is shaven, as also his chin; but he either has a pair of whiskers coming right down to his jaws, or else his cheeks are clean-shaven, and what looks like whiskers is merely shadow.

The sinister supporter is a counterpart of the one just described, so far as regards head-dress, hair, and character of face. He wears a short jacket with plain sleeves, and above it is a plaid which, apparently crossing both shoulders, is belted in at the waist and then hangs as a kilt, coming down to about half-way between his waist and his knees. He has a pair of tartan stockings, whose vandyked tops reach to his knees, below which they are fastened by plain garters. He wears a pair of plain, low-heeled shoes. On his left arm he bears a round Highland target, studded with nails, and at his right hip there hangs a large quiver, full of arrows, which is suspended from a shoulder-belt coming from the left shoulder. His right arm supports the sinister side of the shield.

Nisbet himself states that the supporters of the shield of Skene of that Ilk are ‘two heighlandmen he on the dexter side in a heighland gentlemans dress holding in his right hand a skeen point dounward and the other on the sinister in a servants dress with his Darlach [quiver] and a Target on his left Arm.’ Referring to these seventeenth-century figures, and to Nisbet’s definition of them, Lord Archibald Campbell observes: ‘It is impossible to conceive of evidence of a more conclusive and satisfactory character than that here adduced of the existence of both modes of dress at this period; and of the rank of the respective wearers.’

Cleland, the Covenanting colonel who was killed while in command of the Cameronians in their defence of Dunkeld against the Jacobite Highlanders in 1689, clearly regarded the trews as a sign of rank, and not as a dress of the common people.

This appears in the doggerel verses which he wrote in 1678, describing the 'Highland Host.’ After referring in slighting terms to the half-clad appearance of the ordinary clansmen, he goes on to say:

It will be seen that Martin does not speak of the trews as peculiar to any one class. Captain Burt, however, writing a little later, regards this variety of the Highland dress as almost, if not altogether, a mark of gentry. He remarks thus:

‘Few besides gentlemen wear the trowze, that is, the breeches and stockings all of one piece and drawn on together; over this habit they wear a plaid, which is usually three yards long and two breadths wide, and the whole garb is made of chequered tartan or plaiding; this, with the sword and pistol, is called a full dress, and to a well-proportioned man, with any tolerable air, it makes an agreeable figure; but this you have seen in London, and it is chiefly their mode of dressing when they are in the Lowlands, or when they make a neighbouring visit, or go any where on horseback; but those among them who travel on foot, and have not attendants to carry them over the waters, vary it into the quelt.’ Burt then goes on to describe the kilt or ‘quelt,’ which he speaks of as ‘the common habit of the ordinary Highlanders.’

Another writer, J. Macky, who made a ‘Journey through Scotland ’ sometime in the reign of George I., gives a companion picture to Burts. Macky writes as an Englishman, and apparently he was one, in spite of his name. Of the dress of the people of Lochaber and the Great Glen he writes as follows: ‘The universal Dress here is a striped Plad, which serves them as a Covering by Night, and a Cloak by Day. The Gentry wear Trousings, which are Breeches and Stockings of one piece of the same striped Stuff; and the common People have a short Hose, which reaches to the Calf of the Leg, and all above is bare.’

A little later, Macky found himself in Crieff, with regard to which visit he makes the following observation: ‘The Highland Fair of Crieff happening when I was at Stirling, I had the Curiosity to go see it. . . . The Highland Gentlemen were mighty civil, dress’d in their slash’d short Waistcoats, a Trousing (which is, Breeches and Stockings of one Piece of strip’d Stuff) with a Plaid for a Cloak, and a blue Bonnet. They have a Ponyard Knife and Fork in one Sheath, hanging at one side of their Belt, their Pistol at the other, and their Snuff-Mill before; with a great broad Sword by their side.’ He then goes on to describe the common men who followed these gentlemen:

‘Their Attendance were very numerous, all in Belted Plaids, girt like Womens Petticoats down to the Knee; their Thighs and Half of the Leg all bare. They had also each their broad Sword and Ponyard, and spake all Irish, an unintelligible language to the English. However, these poor Creatures hir’d themselves out for a Shilling a Day, to drive the Cattle to England, and to return home at their own Charge.’

It is noteworthy that Macky, who (like Captain Burt) writes as an Englishman, finds it necessary to explain to his English readers (as Burt also does) what trews or ‘trousings’ are; the fact being that Englishmen then wore knee-breeches, and did not use trousers until about a century later.

It has been seen that the portraits of Cluny Macpherson of 1661, and of a Fraser chieftain living about the dawn of the seventeenth century, represent each as attired in what Nisbet calls ‘a heighland gentleman’s dress.’ Other portraits bearing similar testimony are the following, all representing gentlemen of the eighteenth century: James, 6th Earl of Perth and Duke of Perth (the original being preserved in Drummond Castle), Normand, 19th Laird of MacLeod, painted by Allan Ramsay (preserved in Dunvegan Castle), one of the young sons of MacDonald of the Isles (the original, painted in 1750, being in Armadale Castle), and Sir John Sinclair, Bart., of Ulbster, painted by Raeburn in 1795. This last picture is here reproduced. These are only some notable instances illustrating the attire which had long been specially associated with the gentry of the Scottish Highlands; and it is worth pointing out, as a fact not sufficiently realised, that a man may be of unimpeachable Highland lineage without any of his ancestors having ever worn the kilt.

Among civilians, the fashion of wearing the trews may be said to have ceased with the eighteenth century. The last Macdonell of Glengarry wore the trews (elegantly finished in a fringe above the ancle) when he was a boy; but he appears to have decided in favour of the kilt in later life. In our kilted regiments the trews is still the dress of mounted officers; and in its ungraceful form of modern trousers it constitutes part of the undress uniform of the junior officers and the men. In this form, also, it is worn on all occasions by a few Scottish regiments of Highland origin. It is not unlikely that the modern use of the trews, or of tartan trousers, by privates as well as officers, is in some measure due to the influence of Sir John Sinclair, who insisted on the trews as the dress of all ranks in his Caithness Fencibles, which regiment was raised by him in 1794. In spite of the fact that the trews was then or previously regarded as characteristic of the upper class in the Highlands, Sir John did not recognize such a distinction. Of its superior antiquity to the kilt he had no doubt, and strenuously asserted this doctrine in a pamphlet referred to in the Memoirs by his son David MacRitchie.

Note.—Since the preceding article was written, I have seen M. D’Arbois de Jubainville’s Les Celtes (Paris, 1904), a chapter of which is devoted to the history of Le Pantalon Gaulois. The author makes it quite clear that he refers to trousers reaching down to the ancle; and not to culottes, or knee-breeches. He points to the use of trousers by the Gauls as early as the third century B.C., at which time they also wore mantles, or plaids, for the upper part of the body. But he asserts that the Gauls derived this nether garment from the Germans, who in turn had derived it from the Scythians, and these from the Iranians of Persia. He also shows that the Amazons are represented as wearing trousers. The Gaelic word triubhas (Anglicised as ‘ trews ’) he derives from Old French trebus, Mediaeval Latin tribuces and tribucus, and Low Latin tubrucus,—analysed by him as tu-brucus, i.e. ‘ thigh-breeches.’ Braca he derives, through German, from an Indo-European root bhrdg. He is wrong, however, when he states that ‘ the trews or breeches, in Ireland and among the Gaels of Scotland, was borrowed from the English in recent times.’ Shakespeare, who, like the rest of his countrymen, wore knee-breeches, speaks of the ‘strait trossers’ of the ‘kernes of Ireland.’ {King Henry V., Act iii., Sc. 7.)

I would also add that the two Highlanders who figure in the ornamental title of Blaeu’s map of Scotia, published in 1654, are both represented as wearing tartan breeches. But as, in each case, the tartan of the legs differs from that of the thighs, it is evident that they are supposed to be wearing knee-breeches, not trews.

D. MCR.

That's it for this week and as the weekend is almost here hope it's a good one for you.

Alastair

http://www.electricscotland.com/

Electric Scotland News

I've actually been reading rather than publishing this week. I got hooked on reading the biography of Lord Strathconna and Mount Royal which was a very enjoyable read. I'd previously put up a biography about him but that one almost ignored his early life in both Scotland and Canada. I was also taken with all the work he did for Newfoundland to promote the area economically. He also created an experimental farm which demonstrated that you could live well as long as you were well organised and so as one person put it when visiting him he enjoyed all the best in beef, pork and lamb along with fresh vegetables. I've made this book available and you'll see a link to it below.

-----

And as this coming Saturday usually sees the Burns Suppers being celebrated all over the world I've made available a great book by the Rev. Paul who is credited with starting the Burns Suppers. The book is...

The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns with a Life of the Author

Containing a Variety of Particulars, drawn from sources inaccessible by former Biographers to which is subjoined an Appendix of a Panegyrical Ode, and a demonstration of Burns' Superiority to every other poet as a writer of Songs, by Rev. Hamilton Paul, Minister of Broughton, Glenholm & Kilbuch (1819)

You can download this book from http://www.electricscotland.com/burns/paul.htm

Electric Canadian

The Life of Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal

When I first put up a biography of Lord Strathcona his early life was very bare of facts. I found a new book which now lets us learn much more about him both in his early days in Scotland but also in Canada. I now realise just how much he helped Newfoundland to grow their economy.

And so have now added this single volume work to the foot of his page at:

http://www.electriccanadian.com/make...cona/index.htm

In the Rocky Mountains

By W. H. G. Kingston (1878)

I just happened to find this book and thought it would make an interesting read so have made it available on the site for you to download at http://www.electriccanadian.com/pion..._Mountains.pdf

Electric Scotland

Scottish Reminincenses

By Sir Archibald Geikie (1904)

Now completed this book by adding the final chapters.

You can read this book at http://www.electricscotland.com/hist...bald/index.htm

Enigma Machine

Have added puzzle 95 which you can get to at:

http://www.electriccanadian.com/life.../enigma095.htm

Beth's Newfangled Family Tree

Got in Section 2 of the February 2015 issue which you can read at http://www.electricscotland.com/bnft

I might add that we got this in last week but Beth discovered she'd made some errors so has now released a new copy.

Kincardinshire

By George H. Kinnear, F.E.I.S. (1921). A new book we're starting.

Mr Kinnear’s death when he had written the text of this volume, but had not finally revised it, left the work to be completed by the general editor. Fortunately, the changes which Mr Kinnear intended to make were clearly marked; and these have been closely followed. As it has been impossible to find an accurate list of those who, by advice or otherwise, assisted Mr Kinnear, will all who did so kindly accept this general acknowledgment of their much-appreciated help?

The general editor is deeply indebted to his friend, Mr J. B. Philip, himself a son of the Mearns, who has given unstintedly of his full knowledge of the county and has rendered invaluable service in the reading of the proofs. In addition, Mr Philip generously presented a number of his own photographs for use in illustration.

W. MURISON

November 1920

As many of you will know I'm always looking for histories of places in Scotland and this is such a one that fills a gap. You can view this at http://www.electricscotland.com/hist...hire/index.htm

Notable Orcadians

From Around the Orkney Peat-Fires.

I came across this account which is about a group of Orcadians sitting around a peat fire talking about noteable Orcadians. I enjoyed the telling of the stories so decided to add this to our Orkney page. Here is how it starts...

One wild blustering night many winters ago a number of neighbours had gathered around a rousing peat-fire in the Herston district of South Ronaldshay. The conversation, as was quite natural, brought up the name of the Rev. John Gerard. One of the company, looking across the fire at old Watty Sinclair, asked that worthy whether he knew this once famous minister.

Slowly laying aside his pipe, and gazing at his questioner with open-eyed amazement at his ignorance (whether assumed or otherwise we need not stay to inquire), Watty exclaimed— “ Did I know Mr Gerard? Man, you might as well have asked if I know my own wife or my own bairns. A more sensible question would have been, Is there anybody in South Ronald-shay or in Orkney, that has not heard of him?”

It was quite plain that Watty was very much out of temper because such ignorance had been imputed to him. He had well-nigh worshipped Mr Gerard in life, and now that the eccentric old minister was gathered to his fathers, Watty would gladly have transformed him into an Orkney saint.

Mansie Louttit, who was a man of tact, and was well aware of his old friend’s peculiarities, mildly suggested that it would be well if the rising generation knew more of Mr Gerard than they did; and he was sure there was no one in Orkney better fitted to give that gentleman’s biography than Watty Sinclair.

This bit of flattery somewhat mollified Watty, and, as he was pressed by all present to tell the story of Mr Gerard’s life-work in the county, he cleared his throat, and began : —

You can read this at http://www.electricscotland.com/hist...ey/notable.htm

The Poetical Works of Thomas Aird

By The Rev Jardine Wallace.

I got an email in about another person that I'm researching which mentioned this person to me and so did some research and found a book of his poems which also included a memorial about him. I've ocr'd in this onto the site and also made available the whole book for you to download.

You can get to this at http://www.electricscotland.com/poetry/aird_thomas.htm

THE STORY

I've often wondered why more Scots don't wear this dress rather than the kilt and have often thought of getting this myself. As you'll read in the following article it is a quite ancient dress and an early use of tartan.

The Celtic Trews

An article from the Scottish Historical Review

WHEN the Baron of Bradwardine complimented Waverley upon the handsome figure he presented when fully attired as a Highland gentleman, he incidentally drew a comparison between the respective merits of the kilt and the trews, giving his decision in favour of the latter. ‘Ye wear the trews,’ he observed, ‘a garment whilk I approve maist of the twa, as mair ancient and seemly.’ There may be a difference of opinion at the present day as to which of these two varieties of Highland garb is the more seemly, but there is no doubt as to the antiquity of the trews, regarded as a part of the Celtic dress. Scott himself, speaking in his own person, states that Waverley had ‘now fairly assumed the “garb of old Gaul,” ’and there is sufficient evidence that this statement is correct, making due allowance for some modifications in vogue in the eighteenth century, and introduced at one time or another during that period and the immediately preceding centuries.

The dress of the Celts of Western Europe, about 2000 years ago, has been described by Mr. Charles Elton; his statements being drawn from such authorities as Diodorus Siculus, Pliny, and Pausanias, and from such evidences as the pictures on the medals of the Roman emperor Claudius. Mr. Elton writes as follows:

‘The men and women wore the same dress, so far as we can judge from the figures on the medals of Claudius. When Britannia is represented as a woman the head is uncovered and the hair tied in an elegant knot upon the neck; where a male figure is introduced the head is covered with a soft hat of a modern pattern. The costume consisted of a blouse with sleeves, confined in some cases by a belt, with trousers fitting close at the ankle, and a tartan plaid fastened up at the shoulder with a brooch.’ This form of Celtic dress is of special interest to all who are connected with the Scottish Highlands. Because, while it may have been worn by Continental Celts for many centuries after the date of Claudius, it eventually vanished from the Continent, and from all other parts of the British Isles except the Scottish Highlands, where it continued to be worn without any radical variation down to our own times.

The authority whom I have just quoted continues thus, with reference to the Celts of 2000 years ago: ‘The Gauls were experts at making cloth and linen. They wove their stuffs for summer, and rough felts or druggets for winter-wear, which are said to have been prepared with vinegar, and to have been so tough as to resist the stroke of a sword. We hear, moreover, of a British dress, called guanacum by Varro, which was said to be ‘woven of divers colours, and making a gaudy show.’ They had learned the art of using alternate colours for the warp and woof so as to bring out a pattern of stripes and squares. The cloth, says Diodorus, was covered with an infinite number of little squares and lines, ‘as if it had been sprinkled with flowers,’ or was striped with crossing bars, which formed a chequered design. The favourite colour was red or a ‘pretty crimson.’ In the words of Pliny, ‘Behold the French inhabiting beyond the Alps have invented the means to counterfeit the purple of Tyrus, the scarlet also and the violet in grain; yea, and to set all other colours that can be devised, with the juice only of certain herbs, such colours as an honest-minded person has no cause to blame, nor the world reason to cry out upon.’ ‘They seem to have been fond of every kind of ornament,’ continues Elton. ‘They wore collars and “torques ” of gold, necklaces and bracelets, and strings of brightly-coloured beads, made of glass or of “a material like the Egyptian porcelain.” A ring was worn on the middle finger [at one period, but in a later generation] the fashion changed, and that finger was left bare while all the rest were loaded.’

Such, then, was the attire of the Celts of 2000 years ago in time of peace. Of their armour, offensive and defensive, it would be out of place to speak here.

The accounts just cited, therefore, show us that the tartan was in full swing at that period in all its varied colours; red or crimson being chiefly preferred. And the dress was a sleeved blouse, often belted, with a tartan plaid thrown over it; the lower limbs being clad in trews, closely fitting at the ancle.

This last item requires to be emphasized, owing to popular misconceptions, not only among illiterate Cockneys, but also among many educated people in England, Scotland, and elsewhere. The Celtic people whom Pliny styles (in Holland’s words) ‘the French beyond the Alps’ were remarkable in the eyes of the Romans from the circumstance of their wearing the trews, an article of apparel of which the Romans were innocent. At Rome the word transalpinus, or ‘a person living beyond the Alps,’ was a synonym for ‘a person wearing breeches or trousers.’ The Celtic druids were nicknamed ‘the long-trousered philosophers’ and the Celts as a people were further nicknamed Bracati or Gentes Braccatae, ‘the trousered people.’ On the other hand, the Roman dress was the toga, or mantle, and the belted tunic, a garb very closely resembling the plaid and kilt which in later centuries became associated with at least one branch of the Celtic nation. So averse, indeed, was the early Roman to the restrictions of the nether garments of the Celts, that the first Roman emperor who so far forgot himself as to wear breeches at once raised against him a perfect storm of popular indignation. In fact it would seem to be the case that the wearing of these articles of apparel is a custom which the people of Europe have inherited from the Celts.

Whatever may have been the custom in the days of the Emperor Claudius, the trews has long ceased to be worn by Celtic ladies, unless occasionally in a metaphorical sense. One exceptional instance, it is true, is that of Miss Jeanie Cameron, whose name is so much associated with that of Prince Charles Edward; for she is pictured as attired 'in a military habit— tartan doublet and trews—fully armed, with a gun in her hand.’ But then, it was understood that she was dressed as a man.

The earliest representation of a trews-wearing Highlander which I am able to indicate seems to date from the sixteenth or possibly the seventeenth century, although the picture upon which this supposition is based was only printed in 1767. Curiously enough, it comes from Germany, having been printed on one of a pack of playing cards published in Nuremberg. It is entitled ‘Ein boser Berg-Schott,’ ‘a fierce Scottish Highlander.’ The figure is that of a man wearing what is clearly meant to be a tartan plaid and tartan trews, with a cap or bonnet, in which may be discerned the tail feathers of a black-cock. His face is clean-shaven, except for a small moustache. His right hand is engaged in drawing his sword, and with his left hand he is holding a pike, slanting over his shoulder. The butt of a pistol is seen projecting from his belt. One cannot say with certainty when the original of this picture was drawn, but it seems to contain inherent evidence that it describes a Highlander of at least a century before 1767.

The Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland show us, from entries made in August, 1538, the dress then worn by James the Fifth during a hunting excursion in the Highlands. He wore a ‘short Highland coat’ of parti-coloured velvet, lined with green taffety, trews of ‘Highland tartan,’ and a long and full ‘Highland shirt’ of holland cloth, with ribbons at the wrists. I have here used the word ‘trews,’ but the entry in the accounts is: ‘Item for 3 ells of Highland tartan to be hose to the King’s grace, price of the ell 4 shillings and 4 pence.’ This, I think, clearly indicates the trews. Stockings were known as ‘short hose,’ to distinguish them from ‘hose’ or trews.

‘Defoe, in his “Memoirs of a Cavalier,” written about 1721, and obviously composed from authentic materials, thus describes the Highland part of the Scottish army which invaded England in 1639, at the commencement of the great Civil War. . . . “They were generally tall swinging fellows; their swords were extravagantly and I think insignificantly [i.e. unmeaningly or needlessly] broad, and they carried great wooden targets, large enough to cover the upper part of their bodies. Their dress was as antique as the rest; a cap on their heads, called by them a bonnet, long hanging sleeves behind, and their doublet, breeches, and stockings, of a stuff they called plaid, stripped across red and yellow, with short cloaks of the same. These fellows looked, when drawn out, like a regiment of Merry-Andrews, ready for Bartholomew fair. There were three or four thousand of these in the Scots army, armed only with swords and targets; and in their belts some of them had a pistol, but no musquets at that time among them.”

The uncomplimentary comparison between these Highland soldiers and ‘Merry Andrews’ is obviously due to the resemblance between a man dressed in tartan trews and a Pantaloon, or Harlequin, in his chequered, tight-fitting suit. It is by no means unlikely that the Harlequin’s dress is a survival of the dress of the Celtic juggler. The prevailing colour in the tartan of these troops of 1639 is described as red and yellow. This suggests the MacMillan Clan. The M‘Leods, however, are most prominently associated with the Royalist cause during the English campaigns, and it is well known that, owing to the heavy losses sustained by them when fighting for King Charles at the Battle of Worcester in 1651, the M‘Leods were held exempt from warfare by the other western clans until time had tended to increase their numbers.

The portrait of Andrew Macpherson of Cluny, of the year 1661, gives one a good idea of the trews-wearing Highlander of this period. Somewhere about this period, also, ought to be placed the portrait of Fraser of Castle Leathers, which hangs in the Town Hall of Inverness. This chieftain is dressed in a slashed coat and waistcoat, with tartan trews, and he has also a small sporran or purse. The sporran seems to have been frequently worn with the trews.

If Defoe is right in picturing the whole of the 3000 or 4000 Highlanders in the Scottish army of 1639 as wearing the trews, he indicates that that garment was then common to all ranks. Such, however, was not the case in later years, as may be seen from many references.

Lord Archibald Campbell gives a reproduction of the two supporters of the arms of Skene of that Ilk, as these were pictured in Nisbet’s Heraldic Plates in 1672. The dexter supporter shows a man wearing a flat round cap or bonnet, a short plaid crossing his chest from the left shoulder to the right hip, its under fold coming from the right arm-pit down to the basket-hilt of his broadsword, which hangs at his left hip, suspended from a long shoulder-belt, apparently of ornamented leather, put on above the plaid. The plaid was fixed by a brooch or a silver bodkin, at its point of crossing on the breast; but this is not visible in the picture. The shoulder-belt is of course suspended from the right shoulder. He wears a short coat or jacket, having the sleeves slashed about halfway up, and with ruffs at the wrist. Possibly, however, these are the edges of his gauntlets. His costume is completed by a pair of tartan trews, with garters, the bows of which are very prominent, and his feet are encased in high-heeled shoes. In his right hand he holds a drawn dirk, the point downward; and his left supports the dexter side of the shield. It may be added that his hair hangs down to his shoulders, his upper lip is shaven, as also his chin; but he either has a pair of whiskers coming right down to his jaws, or else his cheeks are clean-shaven, and what looks like whiskers is merely shadow.

The sinister supporter is a counterpart of the one just described, so far as regards head-dress, hair, and character of face. He wears a short jacket with plain sleeves, and above it is a plaid which, apparently crossing both shoulders, is belted in at the waist and then hangs as a kilt, coming down to about half-way between his waist and his knees. He has a pair of tartan stockings, whose vandyked tops reach to his knees, below which they are fastened by plain garters. He wears a pair of plain, low-heeled shoes. On his left arm he bears a round Highland target, studded with nails, and at his right hip there hangs a large quiver, full of arrows, which is suspended from a shoulder-belt coming from the left shoulder. His right arm supports the sinister side of the shield.

Nisbet himself states that the supporters of the shield of Skene of that Ilk are ‘two heighlandmen he on the dexter side in a heighland gentlemans dress holding in his right hand a skeen point dounward and the other on the sinister in a servants dress with his Darlach [quiver] and a Target on his left Arm.’ Referring to these seventeenth-century figures, and to Nisbet’s definition of them, Lord Archibald Campbell observes: ‘It is impossible to conceive of evidence of a more conclusive and satisfactory character than that here adduced of the existence of both modes of dress at this period; and of the rank of the respective wearers.’

Cleland, the Covenanting colonel who was killed while in command of the Cameronians in their defence of Dunkeld against the Jacobite Highlanders in 1689, clearly regarded the trews as a sign of rank, and not as a dress of the common people.

This appears in the doggerel verses which he wrote in 1678, describing the 'Highland Host.’ After referring in slighting terms to the half-clad appearance of the ordinary clansmen, he goes on to say:

‘But those who were their chief Commanders,

As such who bore the pirnie standarts,

Who led the van, and drove the rear,

Were right well mounted of their gear;

With brogues, trues, and pirnie plaides,

With good blew bonnets on their heads,

Which on the one side had a flipe

Adorn’d with a tobacco pipe,

With durk, and snap work [pistol], and snuff mill,

A bagg which they with onions fill,

And, as their strick observers say,

A tupe horn fill’d with usquebay ;

A slasht out coat beneath her plaides,

A targe of timber, nails and hides

With a long two-handed sword,

As good’s the country can affoord;

Had they not need of bulk and bones,

Who fight with all these arms at once?’

Martin refers to the trews as worn by some of the Western Islanders in the reign of Queen Anne. ‘Many of the people wear trowis,’ he says, ‘some have them very fine woven, like stockings of those made of cloth; some are coloured, and others striped: the latter are as well shaped as the former, lying close to the body from the middle downwards, and tied round with a belt above the haunches. There is a square piece of cloth which hangs down before.’As such who bore the pirnie standarts,

Who led the van, and drove the rear,

Were right well mounted of their gear;

With brogues, trues, and pirnie plaides,

With good blew bonnets on their heads,

Which on the one side had a flipe

Adorn’d with a tobacco pipe,

With durk, and snap work [pistol], and snuff mill,

A bagg which they with onions fill,

And, as their strick observers say,

A tupe horn fill’d with usquebay ;

A slasht out coat beneath her plaides,

A targe of timber, nails and hides

With a long two-handed sword,

As good’s the country can affoord;

Had they not need of bulk and bones,

Who fight with all these arms at once?’

It will be seen that Martin does not speak of the trews as peculiar to any one class. Captain Burt, however, writing a little later, regards this variety of the Highland dress as almost, if not altogether, a mark of gentry. He remarks thus:

‘Few besides gentlemen wear the trowze, that is, the breeches and stockings all of one piece and drawn on together; over this habit they wear a plaid, which is usually three yards long and two breadths wide, and the whole garb is made of chequered tartan or plaiding; this, with the sword and pistol, is called a full dress, and to a well-proportioned man, with any tolerable air, it makes an agreeable figure; but this you have seen in London, and it is chiefly their mode of dressing when they are in the Lowlands, or when they make a neighbouring visit, or go any where on horseback; but those among them who travel on foot, and have not attendants to carry them over the waters, vary it into the quelt.’ Burt then goes on to describe the kilt or ‘quelt,’ which he speaks of as ‘the common habit of the ordinary Highlanders.’

Another writer, J. Macky, who made a ‘Journey through Scotland ’ sometime in the reign of George I., gives a companion picture to Burts. Macky writes as an Englishman, and apparently he was one, in spite of his name. Of the dress of the people of Lochaber and the Great Glen he writes as follows: ‘The universal Dress here is a striped Plad, which serves them as a Covering by Night, and a Cloak by Day. The Gentry wear Trousings, which are Breeches and Stockings of one piece of the same striped Stuff; and the common People have a short Hose, which reaches to the Calf of the Leg, and all above is bare.’

A little later, Macky found himself in Crieff, with regard to which visit he makes the following observation: ‘The Highland Fair of Crieff happening when I was at Stirling, I had the Curiosity to go see it. . . . The Highland Gentlemen were mighty civil, dress’d in their slash’d short Waistcoats, a Trousing (which is, Breeches and Stockings of one Piece of strip’d Stuff) with a Plaid for a Cloak, and a blue Bonnet. They have a Ponyard Knife and Fork in one Sheath, hanging at one side of their Belt, their Pistol at the other, and their Snuff-Mill before; with a great broad Sword by their side.’ He then goes on to describe the common men who followed these gentlemen:

‘Their Attendance were very numerous, all in Belted Plaids, girt like Womens Petticoats down to the Knee; their Thighs and Half of the Leg all bare. They had also each their broad Sword and Ponyard, and spake all Irish, an unintelligible language to the English. However, these poor Creatures hir’d themselves out for a Shilling a Day, to drive the Cattle to England, and to return home at their own Charge.’

It is noteworthy that Macky, who (like Captain Burt) writes as an Englishman, finds it necessary to explain to his English readers (as Burt also does) what trews or ‘trousings’ are; the fact being that Englishmen then wore knee-breeches, and did not use trousers until about a century later.

It has been seen that the portraits of Cluny Macpherson of 1661, and of a Fraser chieftain living about the dawn of the seventeenth century, represent each as attired in what Nisbet calls ‘a heighland gentleman’s dress.’ Other portraits bearing similar testimony are the following, all representing gentlemen of the eighteenth century: James, 6th Earl of Perth and Duke of Perth (the original being preserved in Drummond Castle), Normand, 19th Laird of MacLeod, painted by Allan Ramsay (preserved in Dunvegan Castle), one of the young sons of MacDonald of the Isles (the original, painted in 1750, being in Armadale Castle), and Sir John Sinclair, Bart., of Ulbster, painted by Raeburn in 1795. This last picture is here reproduced. These are only some notable instances illustrating the attire which had long been specially associated with the gentry of the Scottish Highlands; and it is worth pointing out, as a fact not sufficiently realised, that a man may be of unimpeachable Highland lineage without any of his ancestors having ever worn the kilt.

Among civilians, the fashion of wearing the trews may be said to have ceased with the eighteenth century. The last Macdonell of Glengarry wore the trews (elegantly finished in a fringe above the ancle) when he was a boy; but he appears to have decided in favour of the kilt in later life. In our kilted regiments the trews is still the dress of mounted officers; and in its ungraceful form of modern trousers it constitutes part of the undress uniform of the junior officers and the men. In this form, also, it is worn on all occasions by a few Scottish regiments of Highland origin. It is not unlikely that the modern use of the trews, or of tartan trousers, by privates as well as officers, is in some measure due to the influence of Sir John Sinclair, who insisted on the trews as the dress of all ranks in his Caithness Fencibles, which regiment was raised by him in 1794. In spite of the fact that the trews was then or previously regarded as characteristic of the upper class in the Highlands, Sir John did not recognize such a distinction. Of its superior antiquity to the kilt he had no doubt, and strenuously asserted this doctrine in a pamphlet referred to in the Memoirs by his son David MacRitchie.

Note.—Since the preceding article was written, I have seen M. D’Arbois de Jubainville’s Les Celtes (Paris, 1904), a chapter of which is devoted to the history of Le Pantalon Gaulois. The author makes it quite clear that he refers to trousers reaching down to the ancle; and not to culottes, or knee-breeches. He points to the use of trousers by the Gauls as early as the third century B.C., at which time they also wore mantles, or plaids, for the upper part of the body. But he asserts that the Gauls derived this nether garment from the Germans, who in turn had derived it from the Scythians, and these from the Iranians of Persia. He also shows that the Amazons are represented as wearing trousers. The Gaelic word triubhas (Anglicised as ‘ trews ’) he derives from Old French trebus, Mediaeval Latin tribuces and tribucus, and Low Latin tubrucus,—analysed by him as tu-brucus, i.e. ‘ thigh-breeches.’ Braca he derives, through German, from an Indo-European root bhrdg. He is wrong, however, when he states that ‘ the trews or breeches, in Ireland and among the Gaels of Scotland, was borrowed from the English in recent times.’ Shakespeare, who, like the rest of his countrymen, wore knee-breeches, speaks of the ‘strait trossers’ of the ‘kernes of Ireland.’ {King Henry V., Act iii., Sc. 7.)

I would also add that the two Highlanders who figure in the ornamental title of Blaeu’s map of Scotia, published in 1654, are both represented as wearing tartan breeches. But as, in each case, the tartan of the legs differs from that of the thighs, it is evident that they are supposed to be wearing knee-breeches, not trews.

D. MCR.

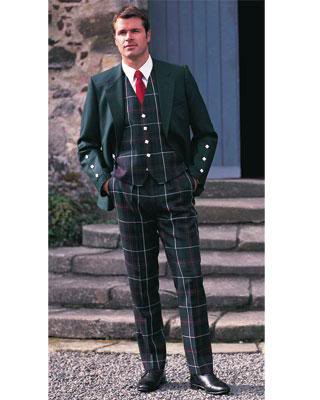

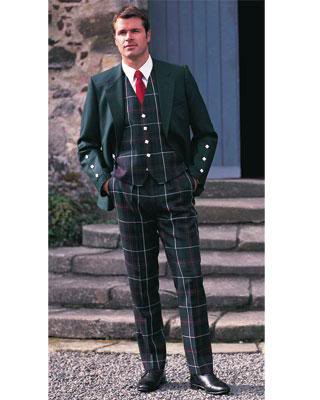

Regular style tartan trews with an Argyll style jacket and 5-button tartan waistcoat (not cut on the bias), for a less highly formal look.

Fishtail style trews with coatee, 3-button tartan waistcoat cut on the bias - note the Chelsea boots.

Mr Salmond wore the eye-catching trousers to a Caledonian Society black tie ball in Beijing in Dec. 2011

REGIMENTAL TREWS

The Regimental Trews are a classic and stylish alternative to a kilt

Fishtail style trews with coatee, 3-button tartan waistcoat cut on the bias - note the Chelsea boots.

Mr Salmond wore the eye-catching trousers to a Caledonian Society black tie ball in Beijing in Dec. 2011

REGIMENTAL TREWS

The Regimental Trews are a classic and stylish alternative to a kilt

That's it for this week and as the weekend is almost here hope it's a good one for you.

Alastair

Comment